Most people think they understand what drives them—but over 90% of human behavior is governed by unconscious needs we rarely recognize.

From the rush to post on social media to the quiet craving for safety or love, these deeper forces trace back to a universal map of motivation: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

This guide, part of CEOsage’s Self‑Actualization & Human Potential hub, offers a clear explanation of Maslow’s model and practical steps to move from deficiency toward authentic growth.

Let’s dive in…

The Hidden Drivers Behind Human Motivation

We want to believe we know the “why” behind our actions. If asked, we can provide reasons for every action, purchase, or statement we make.

Study after study, however, reveals a different truth: most of the time, we don’t know why we do what we do. That is, we’re unconscious of our real motivations.

Discovering our true motivations can be a sobering experience because doing so challenges the identity we often hold about ourselves.

Example: Why We Buy

For example, you may think you purchased a sweater because you liked the color or fit. In reality, however, you likely bought the item because it reminded you of something: maybe someone you secretly envy (like a celebrity), or someone you subconsciously compete with wore a similar sweater.

We buy particular brands because they evoke a certain feeling in us. The source or trigger of these feelings is largely unknown to us (unconscious).

Denying Subconscious Motivations

Upon reading this, an internal voice may arise, “No. I’m not shallow or superficial like that.” (I have this voice, too.)

We often deny these primary motivations because they are inconsistent with how we perceive ourselves. This denial makes it difficult to observe what forces influence us “below the surface.”

Savvy marketers and advertisers, however, understand these hidden motivations and exploit them to get us to purchase their products.

What Are Maslow’s 5 Basic Human Needs?

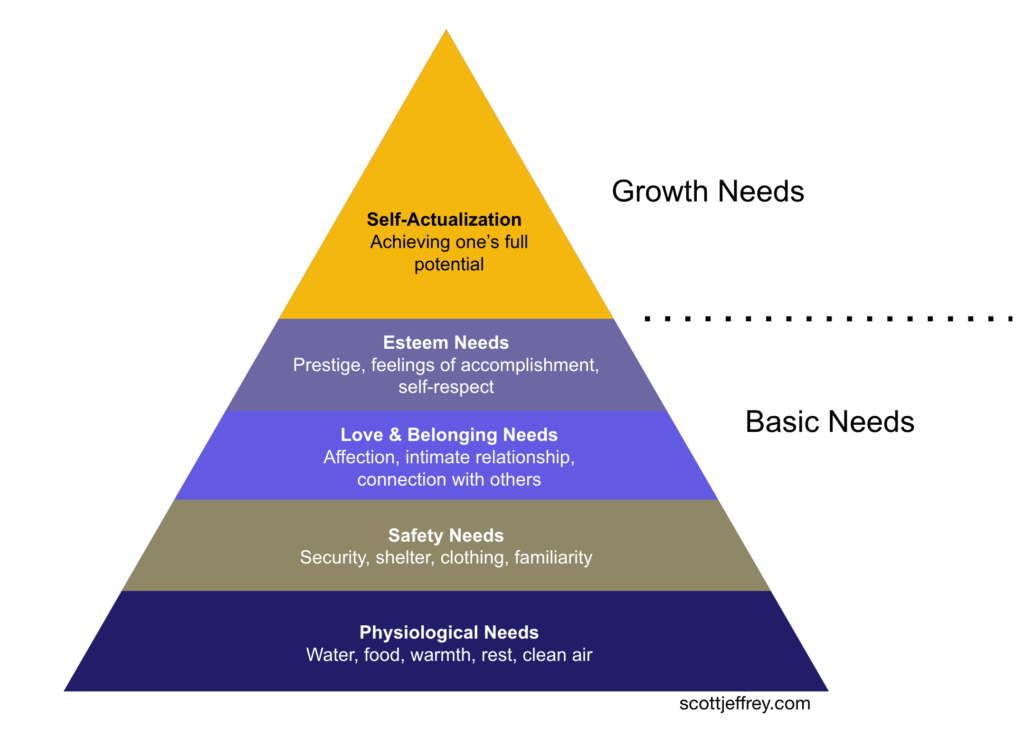

Maslow identified the five primary needs as follows:

- Physiological needs: air, water, food, proper nutrition, homeostasis, and sex.

- Safety needs: shelter, clothes, routine, and familiarity.

- Belonging and love needs: affection and connection to family, friends, and colleagues.

- External Esteem needs: respect from others, recognition, and reputation/prestige.

- Internal Esteem needs: self-respect, high evaluation of oneself, achievement,

Technically, Maslow outlined four basic needs (not 5) in his original treatise.

However, the esteem need has both an internal and external component, so it can be broken into two separate categories (yielding a total of 5 basic needs).

In Maslow’s model, self-actualization is not considered a “basic human need.” Instead, it represents a “growth need,” as we’ll see below.

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Most sources illustrate Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in a triangle, even though Maslow didn’t present it this way.

He did, however, express a hierarchical relationship between the basic human needs, going from the lowest or most basic need (physiological) to higher-level needs.

In A Theory of Human Motivation, Maslow explains:1Maslow, Motivation and Personality, 1954, 83.

At once other (and higher) needs emerge and these, rather than physiological hungers, dominate the organism. And when these in turn are satisfied, again new (and still higher) needs emerge, and so on. This is what we mean by saying that the basic human needs are organized into a hierarchy of relative prepotency.

Now, we’ll explore each of these basic human needs more closely. These needs can appear “academic” until we relate them to our daily experiences.

The 5 Basic Human Needs

All of the needs below self-actualization are basic human needs.

Maslow also called these basic human needs neurotic or deficient needs because if we’re focused on meeting them, we have anxiety.

We don’t feel ourselves, and our life isn’t fulfilling. We can’t operate from a calm, quiet center and lack positive mental health.

Any unmet or ungratified basic human need causes problems and tensions that we seek to resolve.

1 Physiological – Survival

Physiological needs are the requirements of all biological creatures. Without air, water, and food, biological organisms perish.

When we need food, we eat. If we don’t have food, we get anxious.

Physiological Needs Examples

When you have to pee during a flight, and there are six people in front of you waiting in line to use the lavatory, your physiological needs are threatened.

In some parts of the world, many individuals struggle to meet their basic physiological needs. It’s estimated that over a billion people lack access to sufficient food, basic nutrition, or clean water.

Physiological needs can also remain unmet even in individuals who aren’t in an environment of lack.

If, as a child, for example, meals were withheld as a form of punishment, a part of you (a child part) might always be seeking food (even when your body isn’t hungry). In this way, psychological trauma in childhood can threaten our basic human needs in adulthood.

2 Safety – Stability

At its most fundamental level, to meet our safety needs, we need shelter from the elements, clothes to cover our bodies, and some semblance of the familiar.

Safety Needs Examples

If you don’t have enough money to pay for rent (or your mortgage and taxes), clothes (for protection, not fashion), and transportation (to get food and make money), your safety needs aren’t being met.

Once again, many people worldwide are unable to meet these basic human needs. Here, too, there are psychological ways that the basic need for safety goes unmet.

If a part of you felt physically or psychologically unsafe as a child (which is sadly true for many of us), then that part is continually seeking security.

Even as an adult living in your own home, a fearful part of you can make you feel like something terrible is about to happen. For this reason, many adults leave lights on in their homes after dark. It’s also why many people keep televisions, radios, or music running in the background at all times.

Also, when you’re in a period of transition, your basic security needs easily get triggered. Safety implies a certain degree of normalcy and control.

When your need for safety is threatened, you feel out of control. Naturally, you’ll want to get a grip on things. Routines help us do that. But when you’re in the midst of a major life transition—for example, moving, out of work, or getting a divorce—you may feel unsafe.

3 Love and Belonging – Connection

Belonging is a psychological need predominant in adolescence (called identity crisis in Erik Erikson’s model), and this need often remains unmet in adulthood.

Belonging is a feeling of connection with and approval from others. It starts with our immediate family, then branches out to friends, religious groups, and other social groups (like sports teams or clubs). This need to belong later extends into professional relationships and a significant other.

Love and Belonging Needs Examples

When you’re born into a genuinely loving and accepting family and grow up surrounded by mature, mentally healthy adults who can support, guide, and defend you when needed, a feeling of love and belonging can grow within you.

You become that guiding light for those around you in adulthood and can bless others in need. You also no longer need to be around others to feel okay or complete.

But most of us—I day say, virtually all—didn’t have such an experience in childhood (even though we sometimes delude ourselves into believing we did). Our parents may have done the best they could, but they were also psychologically immature, wounded, and unconscious of the majority of their behaviors, thoughts, feelings, and impulses.

As a consequence, most of us have a longing to belong that stems from a fear of being abandoned (which we subconsciously experienced as children).

This unmet need to belong drives us to identify with social groups, religious institutions, and other special-interest groups in adulthood. It also fuels a lot of people’s impulse to invest time in social media.

4 Esteem – Worth

Self-esteem, the last of Maslow’s neurotic needs, dominates most of our behaviors in public. Our image-driven culture pushes us to be more concerned with what other people think than with how we feel about ourselves. We seek approval from others instead of self-acceptance.

Esteem Needs Examples

This unmet basic human need also stems from being rejected and disapproved of during childhood (in explicit or subconscious ways).

For example, unmet external esteem needs influence the majority of Facebook and Instagram usage. Most social media users are posting things they are doing with a subconscious message of “Look at me. Look at how great I am.”

Each person continually compares, competes, and envies others. Numerous research studies link Facebook usage to increased depression and jealousy. These suppressed and repressed emotions get triggered because of an unrecognized basic human need for self-esteem.

If that wasn’t challenging enough, there’s another dimension to our esteem needs: internal esteem, or how we perceive ourselves. All of the judgment, criticism, and rejection we experience from our parents, teachers, and friends as children get internalized as the voice of an “inner parent.”

Some individuals have inner parents who are nurturing, accepting, and understanding, who guide their behavior not with shame and guilt, but with self-compassion. These, however, are a small minority. Most of us have harsher inner parents who scold, berate, and judge us. We often call this voice our inner critic, judge, or saboteur.

5 Self‑Actualization – Fulfillment

Self‑actualization is often mistaken for achievement. In truth, it is integration. Maslow noted that the healthiest people seemed paradoxically humble: they sought truth more than fame, simplicity more than glamour. Their motivation was a devotion to wholeness.

As lower needs cave inward, awareness expands outward. One no longer asks, “What can I get?” but “What wants to emerge through me?” This shift from deficiency to growth transforms desire into creativity.

Sociologically, such individuals stabilize entire cultures—their equilibrium radiates coherence. Maslow called their guiding principles Being‑values: truth, beauty, justice, aliveness, self‑sufficiency. When action expresses these values, life itself becomes art.

True self‑actualization isn’t a summit but a cycle: meeting needs, losing balance, rediscovering order at a higher octave. It’s the spiral of human evolution occurring within a single consciousness.

Assessing Your Current Need Fulfillment

How do you know if you have unmet basic human needs?

Here’s a simple test:

- If you can’t just sit down and “be”—if you feel like you need to constantly be “doing something” or consuming something (food, media, drugs, work, etc.)—your basic needs aren’t being internally gratified.

- Do you feel like you must be in a relationship at all times? Do you find yourself needy or clinging in your primary relationship? This neediness relates to a childhood wound.

- Are you investing at least a portion of your time in internal growth and development? If not, one or more of your basic human needs are unmet.

We all share the same needs. These needs are our birthright as human beings. But when something blocks or challenges these inalienable rights, we begin to exhibit strange behavior.

Driven by fear because we don’t feel accepted, loved, or respected, we often behave irrationally and impulsively in our attempt to resolve an unmet basic human need.

Generally speaking, the true motivation behind our irrational behavior exists outside of our awareness. That is, when something threatens our physiological, safety, social, or esteem needs, we don’t see why we’re behaving as we do.

How Unmet Basic Human Needs Rule Our Behavior

All of the neurotic needs we highlighted above hold us back. They keep us from actualizing our potential and being ourselves.

These unmet basic human needs force us into set patterns of behavior that reflect specific archetypes.

Belonging & Esteem Needs Examples

When we’re overly concerned with how people perceive us, we act in a manner we think will meet their approval.

Different archetypes have different patterns of behavior. If, for example, you have unmet esteem needs, you’re going to seek status and approval from others. If someone in your environment is playing the “cool guy” (or cool girl) archetype, you might copy their behaviors and mannerisms to appear “cool” too.

Or, if someone behaves like an aristocrat (smug, arrogant, elitist, “high society”) and looks down on you, you’ll react in a specific way if you’re unconscious of this esteem need.

You might feel small in comparison to this person, but then you’ll seek out someone else you can dominate to feel better about yourself (in an attempt to raise your internal esteem).

Most of Our Behavior is Unconscious

Keep in mind that these archetypal patterns of behavior mostly operate outside of our conscious awareness—unless you’re doing extensive inner work.

We might think we are behaving one way, but in fact, we are presenting ourselves in an entirely different manner. We often rationalize our motives while our true motivation is hidden from us.

Research suggests that over 95% of our behavior is unconscious.

While this statistic is potentially shocking to the layperson, it’s a basic insight within the field of depth psychology.

The unconscious, not the conscious, rules most of our lives—until we build consciousness.

This insight speaks to the importance of getting to know one’s shadow. The existence of these archetypes—driven by unmet basic human needs and psychic wounds from childhood—is the cause of these unconscious patterns of behavior.

Why Basic Needs Often Plague Us in Adulthood

Psychologist David Richo explains in How To Be An Adult, we’re born with emotional needs—love, safety, acceptance, freedom, attention, validation of our feelings, and physical holding.

These emotional needs form a healthy self-concept, embedded within us on a cellular level.

Originally, they were experienced in a survival context: dependency on others (especially our parents).

The challenge is that these early needs can only be fully fulfilled in childhood (when we’re fully dependent).

As adults, Richo points out, “the needs can be fulfilled only flexibly or partially, since we are interdependent and our needs are no longer connected to survival.”

For most of us, our “inalienable emotional needs” were not met sufficiently in childhood. As adults, we are still trying to meet these basic human needs externally.

Resolving the Tensions of Unmet Needs

However, we can’t meet these basic human needs externally, or rather we can, but only “flexibly or partially.”

Richo continues: “Our problem is not that as children our needs were unmet, but that as adults they are still unmourned!”

That is, it’s the wounded “inner child” within us that’s still holding onto what was missed and causing pain and emotinal tension in our present relationships.

So ultimately, it’s a “Child part” within us that’s driven by these basic needs.

Until we grieve and come to terms with the loss this child experienced, we cannot root ourselves in our Adult part and access our full potential.

Maslow’s Self-Actualization Need

What set Abraham Maslow apart from other psychologists is that he didn’t want to study neurotic people, which was the exclusive focus of his field at the time. (Arguably, the same is the case today.)

Instead, Maslow set out to understand positive mental health. This task required him to seek out individuals who weren’t struggling to meet their basic human needs.

Maslow looked for what he called self-actualizing people. Self-actualization is the need to become what one has the potential to be.

See this guide on self-actualization for the thirteen characteristics Maslow identified in self-actualizing individuals.

Because self-actualizing individuals were focused on their internal growth instead of meeting their external needs, Maslow classified these people as mentally healthy. However, he found it challenging to find enough of these individuals to study.

Since Maslow, developmental and transpersonal psychologists have also examined these same individuals. Generally speaking, they represent a very small percentage of the population.

What Motivates the Average Person

Basic human needs, such as food, water, sex, shelter, friends, family, and reputation, are all external needs. We cannot meet them within ourselves. We seek to meet these needs through the environment and other people.

As Maslow writes in Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences,

“Basic human needs can be fulfilled only by and through other human beings, i.e., society.”

So what happens once individuals fulfill their basic human needs? The individual’s attention makes a 180-degree turn: their attention shifts from what’s outside to what’s inside of them.

Subconscious questions behind most human activity include:

- What will other people think of me?

- Will others like/approve of me?

- How do I compare myself to others?

Notice how these questions focus on the external world (i.e., basic human needs).

What Motivates Individuals with Positive Mental Health

In contrast, human beings with positive mental health—what Maslow called self-actualizing individuals—are guided by different internal questions:

- What am I really capable of?

- What’s my purpose here?

- How do I find meaning in my life?

- How can I actualize the best version of myself?

Notice how all of these questions relate to the individual. The question of capability or potential isn’t about someone else. When individuals compare themselves to others, external esteem needs, not self-actualization, are motivating their behavior.

From Deficiency to Growth Motivation

At first glance, this shift toward oneself appears selfish or egotistical. But it’s just the opposite.

When Driven By Basic Human Needs …

Individuals necessarily act selfishly when basic human needs drive them.

Why? Because unmet basic needs stem from deficiency, from a feeling of lack, from a fear of not having or being enough.

These basic human needs stem from a prevailing sense of separation, and they tend to trigger the fight-or-flight mechanism in our brains.

When this happens, we can’t assess situations from our more advanced prefrontal cortex because the primitive brain center (the limbic system) is in control.

When Motivated by Growth

Once individuals meet their basic needs, the anxiety that drives these needs falls away. Individuals can then relax into themselves.

The need to impress or get approval from others doesn’t influence their behavior (even though they’re aware that others judge them). They no longer seek a group or an idea to define their identity.

Dropping the need to compare themselves to others, they begin to individuate. They can now establish their unique path to self-mastery.

Psychologically mature adults no longer hold external rules of right and wrong. Instead, they have their internal moral compass, personal values, and ethics based on what Maslow called B-values or being values.

Being values include truth, wholeness, justice, beauty, aliveness, richness, simplicity, effortlessness, and self-sufficiency.

Only such individuals can act genuinely selflessly. Otherwise, our actions are mere posturing, driven by some other unmet needs (usually external esteem or wanting to belong in “civilized societies”).

This shift of attention from basic human needs to growth needs coincides with a shift in an individual’s consciousness.

A Practical Approach to Basic and Growth Needs

The reality is that in daily life, most of us are pursuing all of these basic human needs simultaneously to varying degrees. Instead of focusing on which need you’re attempting to meet, consider the overall direction of your life.

Instead of stacking the needs, one on top of the other, psychologist Clayton Alderfer, illustrated them on a horizontal continuum.

If you’re investing an increasing effort in your growth, you probably feel more satisfied and fulfilled. This satisfaction will likely fuel your growth efforts further.

Research by psychologist Martin Seligman confirms this.

Seligman, the founder of positive psychology, finds that people feel more gratification (lasting happiness) when they are pursuing growth by playing to their natural strengths.

If, however, your emphasis is turning to unmet relatedness and existence needs, your frustration is building. Frustration diminishes your motivation to grow.

Takeaway Lessons from Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Here are four key takeaways based on Maslow’s theory of motivation:

- We are all more alike than we are different. We truly are part of a human family.

- Most of us are feeling more insecure, unloved, and unworthy than we admit to ourselves or others. These unmet basic human needs fuel our unconscious behavior.

- Authentic positive mental health, or mature psychological development, is reached when we resolve these hidden tensions within ourselves. Only then can we access our innate potential as mature adults.

- Focus on your overall life direction. Are you moving in the direction of growth (and feeling greater satisfaction)? Or are you regressing in an attempt to meet your basic human needs and feeling frustrated?

I know there’s a lot to digest in this guide. Reviewing the descriptions of Maslow’s needs above can help you become more conscious of how they operate in your daily life. This self-awareness is key to psychological development.

The Goal of Self-Actualization

If we strip away all of our unmet basic human needs and the drives of the archetypes they represent, we arrive at ourselves:

Authentic human beings with natural abilities and capacities that can be cultivated over time.

As Jungian author Robert Moore used to say in his lectures,

“Being an archetype is easy. Being a human takes work.”

In truth, a self-actualizing individual is more human.

Through psychological development, we strip away everything we are not and learn how to hold the psychic tensions within us.

Jung called this the process of individuation. We separate ourselves or individuate from the archetypes and behavioral patterns of our culture and society to discover what we are—our True Self.

It is in this sacred space that our true humanity lies. It represents an end to fear, unconscious behavior, and needless suffering that we are inflicting on ourselves and others each day.

Self-liberation, then, is the goal of psychological work, and it’s why “know thyself” was an essential dictum in Ancient Greece. It brings us to personal freedom or what the ancients called Moksha (self-liberation). It liberates us from our unconscious motivations and habits of the past. THIS is everyone’s birthright.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The process of self-actualization, individuation, and realizing our potential is synonymous with the hero’s journey. It’s the developmental path from adolescence to full psychological adulthood, which takes heroic persistence, courage, and will.

On this journey, we learn to:

- Confront our fears

- Resolve our anger

- Experience our grief

- Accept our guilt and shame

- Uncover our true motivation

- Assert ourselves

- Integrate different parts of our psyche

- Get to know our shadow

- Pierce through our self-deception

- Locate authority within ourselves (recollect our projections)

To accomplish all of this, we must first cultivate self-awareness and self-leadership, become honest with ourselves, and learn to abide in our center. These practices allow us to reflect on our lives and better understand ourselves.

As this alchemical process unfolds, we walk forward on the path to our unique destiny.

Read Next

The Four Stages of Learning Any Skill on Your Path to Self-Actualization

Peak Experiences & Flow: Maslow’s Formula for Human Potential

Intrinsic Motivation: An In‑Depth Guide with Real‑World Examples

Jungian Synchronicity Explained: The Psychology of Meaningful Coincidences

This guide is part of the Self‑Actualization & Human Potential Series.

Learn evidence‑based frameworks integrating psychology, motivation, and virtue ethics to uncover your highest capacities and cultivate authentic fulfillment.

Scholarly References

- Daniel Kahneman. (2010) Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Bargh JA, Morsella E. The Unconscious Mind. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(1):73–79. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x

- Dylan Walsh, Study: Social media use linked to decline in mental health, MIT Sloan, September 2022.

- Emma Young, “Lifting the lid on the unconscious,” NewScientist, July 25, 2018.

- Alderfer, Clayton P. (1969). “An empirical test of a new theory of human needs.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 4 (2): 142–75.