Why do the same myths, heroes, and gods echo through every civilization?

Carl Jung believed they emerge from an invisible matrix of images—the collective unconscious.

These archetypes aren’t abstract ideas; they are living energies that express themselves through experience, art, and dreams.

This in‑depth CEOsage guide—part of the Jungian Psychology Series—distills Jung’s essential archetypes and shows how to recognize them in your own process of self‑realization.

Let’s dive in …

What Are Jungian Archetypes?

An archetype isn’t a character or a role to imitate. It’s a psychic template—a structure of instinct underlying how we perceive reality. Jung called these patterns the “forms which the instincts assume.”

Each culture dresses these patterns in its own language: myth, religion, literature, or film. But beneath every symbol lies the same architecture—the shared grammar of consciousness itself.

The Collective Unconscious: The Psyche’s Deep Foundation

Below the layers of personal memory lies what Jung named the collective unconscious—a storehouse of inherited images.

Here dwell the primal images—the Mother, the Shadow, the Hero, the Wise Old Man—recurring in every civilization in ancient temples, modern movies, and nightly dreams.

When we begin to sense these invisible designs, the psyche becomes less chaotic. Life turns from a random happening to a meaningful pattern.

Recognizing these deep patterns provides orientation within one’s inner life and a sense of kinship with the human story itself.

As Jung wrote, archetypes “determine individual lives in invisible ways.”

Archetypes, Complexes, and the Process of Individuation

Archetypes are impersonal; complexes are personal. A complex forms when an archetypal energy fuses with our history—our mother, our work, our fears.

The goal of Jungian work isn’t to suppress these forces but to bring them into relationship. This gradual integration is individuation—the movement toward wholeness.

Every authentic transformation follows this same law: consciousness meeting what it once rejected.

The Core Jungian Archetypes

I’ve seen numerous articles online about “12 Jungian archetypes,” which leads the reader to assume that Jung provided 12 archetypes. (I’ll explain where I think this mistake comes from below.)

Jung wrote about numerous archetypes in his work. Later, Jungians analyzed many others. However, he himself did not make a list of archetypes.

In fact, Jung specifically said there’s no point in making or memorizing a list of archetypes. He writes in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious:

It is no use at all to learn a list of archetypes by heart. Archetypes are complexes of experiences that come upon us like fate, and their effects are felt in our most personal life.

So to be clear, there is no definitive list of Jungian archetypes. Technically speaking, every word in the dictionary represents an archetypal form.

That said, the most common archetypes in the Jungian literature, especially in Jung’s work, are:

| The Mother | The Self |

| The Father | The Maiden |

| The Child | The Wise Old Man/Woman |

| The Persona | The Trickster |

| The Shadow | Birth |

| The Anima | Marriage |

| The Animus | Death |

| The Hero |

Let’s examine each archetypal pattern more closely.

Raphael’s The Sistine Madonna (1512)

The Mother

We start with the mother archetype. The Mother (and mother complex) is arguably the most often addressed archetypal pattern in Jungian literature—and for good reason. It is via this powerful archetype that human life comes into being.

This archetype can manifest in many other archetypal forms, including goddess, demon, witch, dragon, vessel, the abyss, tree, garden, fertility, a deep well, an egg, or a womb. Jung explains that the Great Mother image found in religion is also a derivative of the mother archetype.

Jungian writer Robert A. Johnson explains:1Johnson, The Fisher King & the Handless Maiden, 1993, 61.

The mother archetype is the bounty of nature, which gives us our life and all that we need for that life and which is anyone’s legacy by the fact of being alive. The mother archetype is the art of living peaceably with the bounty of nature, which is pure gift and lies within the ecology of the natural order.

For a dedicated treatment of this classic Jungian archetype, see Erich Neumann’s The Great Mother (1955).

The Father

The masculine counterpart to the Mother is the Father, an equally important archetypal pattern that gets far less attention in Jungian literature. The Father represents the spiritual aspect of Man. The father figure represents intelligence, decisiveness, and wisdom.2“The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales,” CW 9i, par. 396.

In the son, a positive father complex leads to a reverence for spiritual values. In the daughter, the Father “exerts his influence on the mind or spirit … increasing her intellectuality.”3“The Origin of the Hero,” CW 5, par. 272.

The Child

The Mother and Father give way to the Child. The child archetype is inextricably linked to both these archetypes, especially the Mother. From Jung’s The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche:4Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 8.

The mother-child relationship is certainly the deepest and most poignant one we know … (the child) is part of the psychic atmosphere of the mother … everything original in the child is indissolubly blended with the mother-image.

The child archetype has many faces and variations, including what Jung called the Eternal Child, or Puer Aeternus—another classic Jungian archetype.

The Persona

The persona represents a person’s social mask. It’s a mask we wear when interacting with the world, especially in the earlier stages of life. Although the persona is singular, we generally wear numerous masks (personae).

An executive, a lawyer, a housewife, an achiever, or an athlete are examples of personas. Instead of representing a role we sometimes play, these personae can become part of our identity—who we think we are. That is, we identify with our persona before starting the individuation process.

The Shadow

The Shadow represents the first of three archetypes of development in Jung’s work. The Shadow is the “dark side” of our personality; it contains everything we are cut off from. In our early development, many primitive impulses, negative emotions, positive attributes, and power drives tend to get repressed.

Everything we deny in ourselves, for whatever reason, becomes part of our Shadow. Anything opposed to our conscious self-identity becomes related to this disowned self. The first part of Jung’s individuation process is to learn to integrate one’s shadow.

While the shadow is a Jungian archetype in a general sense, a pantheon of archetypal figures exists within one’s shadow.

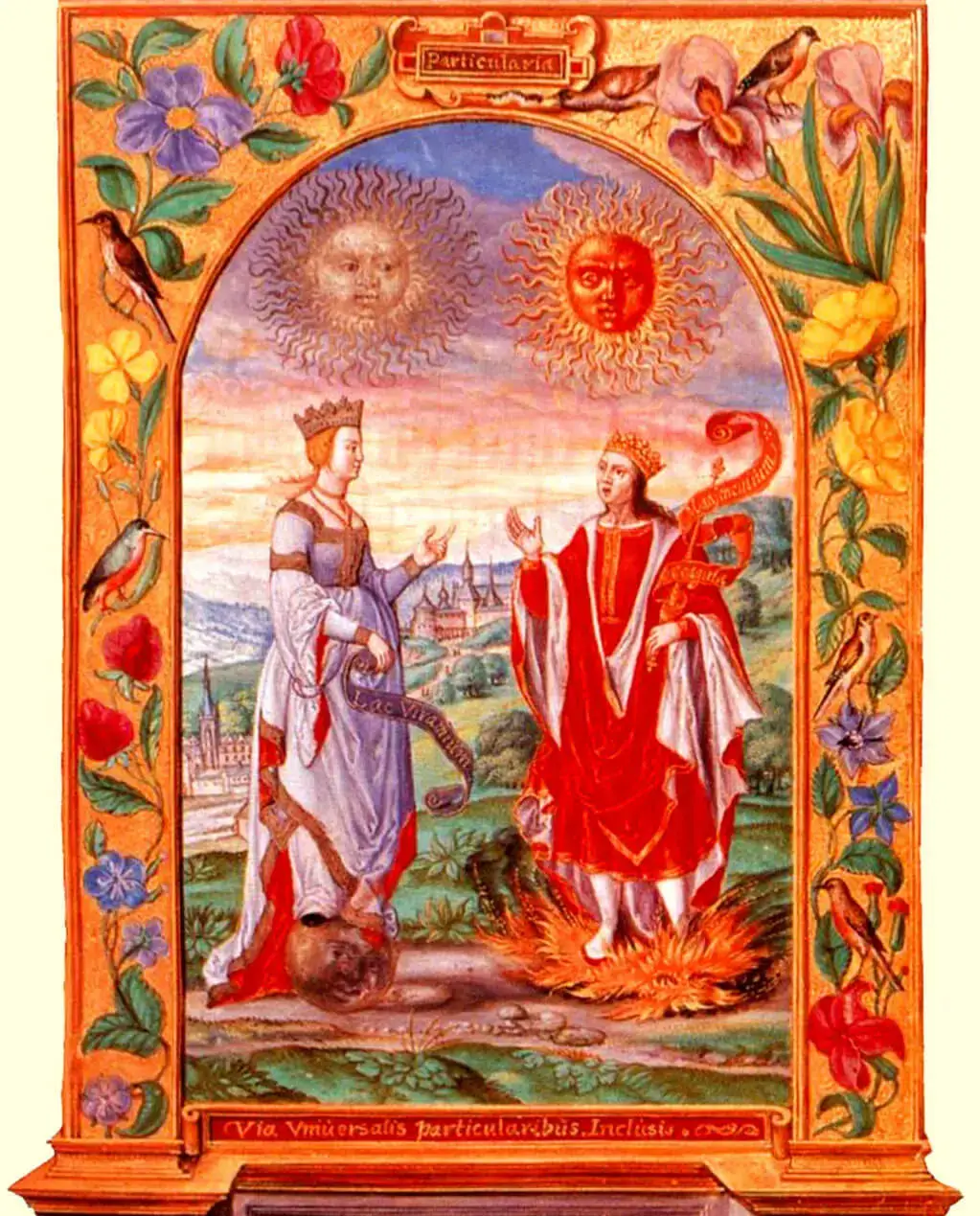

Splendor Solis, Plate 4

The Anima

In Jung’s work, the Anima often takes center stage. The Anima archetype represents the feminine aspect of a man’s unconscious. Anima is Latin for Soul. At its highest, Jung’s Anima represents a man’s muse, inspiration, connection with higher virtue, and source of meaning. From Jung:5Jung, Conversations with C.G. Jung, 30.

To a man the anima is the Mother of God who gives birth to the Divine Child.

However, the anima is bipolar. A man possessed by his Anima becomes moody, emotional, and unstable. His innate masculinity drops away, and he becomes highly irrational. Men possessed by their Anima are wishy-washy, dishonest, and irritable. They often act feminine as well.

The Animus

The Animus archetype is a masculine component of a woman’s unconscious. For a woman, the Animus is the gatekeeper to her spiritual life. The Animus often appears god-like and all-powerful. Jungian Barbara Hannah calls the Animus the “spirit of inner truth in women.”6Barbara Hannah, The Animus, 2011.

A woman possessed by her Animus loses her femininity, her softness. You can not reason with an Animus-possessed woman. She is never content. Jungian Marie-Louise von Franz explains:7Interpretation of Fairy Tales, 55.

The animus contributes to her unrest so that she is never satisfied; one must always do more for an animus-possessed woman.

The Anima-Animus represents the second archetype of development in Jung’s process.

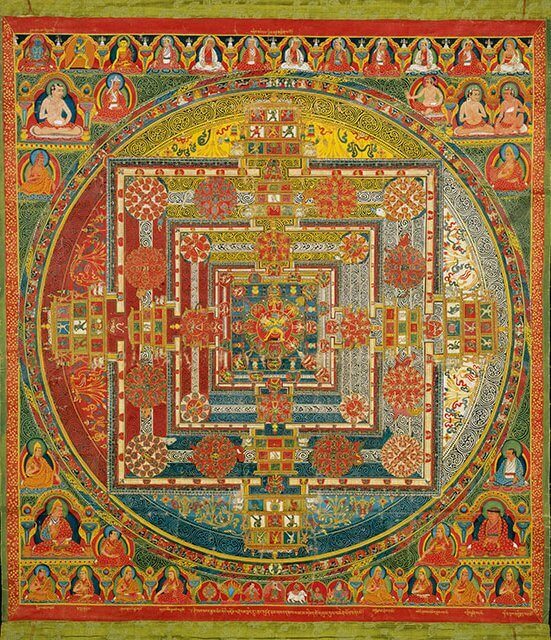

Tibetan Mandala (Symbol of Wholeness in the Psyche)

The Self

The Self is the archetype of wholeness or transcendence. From Jung:8Jung on Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises: Lectures Delivered at ETH Zurich, Volume 7: 1939–1940, 55.

So what is the Self? It is a center or wholeness that consists not only, like consciousness, of the conscious psyche, but of both the conscious and unconscious parts of the psyche together. This Self also comprises what we are but do not know we are.

Jungian psychologist Edward Edinger writes in Ego and Archetype:9Edward F. Edinger. Ego and Archetype (C. G. Jung Foundation Books Series), 1992.

Psychological development in all its phases is a redemptive process. The goal is to redeem by conscious realization, the hidden Self, hidden in unconscious identification with the ego.

From a Jungian perspective, the self is both personal and impersonal. It includes the ego and one’s inner divinity. Arriving at the Self represents the final stage of Jung’s individuation process.

Achilles fighting against Memnon, Leiden Rijksmuseum voor Oudheden

The Hero

Another classic Jungian archetype is the Hero. In storytelling, the hero represents the protagonist or the main character. In psychology, the hero archetype is a universal symbol representing a specific stage of human development. The hero must consolidate his energy to overcome obstacles and achieve specific goals.

Jung writes in Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious:10Jung, The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol. 9 Part 1), 1981.

The hero’s main feat is to overcome the monster of darkness: it is the long-hoped-for and expected triumph of consciousness over the unconscious.

Psychologically, the hero archetype represents the peak of the adolescent stage of development. The young Hero can develop into mature adulthood by engaging in the hero’s journey.

Youth, William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1893)

The Maiden

The Maiden is the woman. She personifies innocence and softness. The simple Maiden meets a man and gives birth to become Mother. She is the feminine component in a man’s psyche and the inspirer of his life. That is, the Maiden represents the Anima for a man.

For both the feminine and the masculine, the Maiden represents one’s feeling function. Jung and the Jungians go into great detail about the “wounded feeling function” in our society. Robert A. Johnson uses the myth of the Handless Maiden to illustrate how the feminine heals: by being still in the forest.11Robert A. Johnson, The Fisher King and the Handless Maiden. The masculine fights; the feminine reconciles.

See also: Feminine Archetypes: Decoding the Feminine Psyche Through Jungian Wisdom

Rembrandt’s Philosopher in meditation

The Wise Old Man

Jung often referred to the Wise Old Man archetype in his work. For Jung, the Wise Old Man was a common manifestation of the Self in one’s psyche—the inner wisdom hidden within us.

In fact, Jung’s unconscious personified this archetype in a character in his dreams and active imagination called Philemon.12See Jung’s The Red Book and Dreams, Memories, Reflections. Philemon helped guide Jung on numerous adventures and led him to many powerful insights he later shared in his writings.

The role of this Wise Old Man (or woman) archetype is to guide the individual toward wholeness. The Sage is another expression of this classic Jungian archetype.

Norse Mythology Image of Loki from SÁM 66 (18th Century)

The Trickster

The trickster is another universal archetypal pattern found throughout antiquity in myths and legends. The Trickster is a complex character with many contradictory dimensions. Jung writes in “On the Psychology of the Trickster-Figure,”13Jung, CW 9i, par. 472.

He is a forerunner of the saviour, and, like him, God, man, and animal at once. He is both subhuman and superhuman, a bestial and divine being, whose chief and most alarming characteristic is his unconsciousness.

The Trickster archetype is sometimes referred to as a puppetmaster or a manipulator. Loki is a popular trickster god in Norse mythology. When someone says “fate is playing a trick on him,” they are alluding to this trickster archetype.

Universal Motifs: Birth, Marriage, Death

Many people mistakenly think that characters are archetypes. For example, one may assume that Loki is the Trickster. Remember that archetypes are formless and impersonal.

While a character can personify archetypal qualities, the character itself is not the archetype. Additionally, characters are not the only expressions of archetypal energy.

Every passage is archetypal. Birth opens consciousness, marriage unites opposites, death dissolves form into meaning—each mirrors psychological transition.

Any kind of initiation ritual is archetypal, too. Many Jungians have analyzed various creation myths—how the universe came into being—to better understand the psyche.

12 Archetypes Model from Carol Pearson

The Modern Confusion: The “12 Jungian Archetypes” Myth

Across websites, ebooks, and brand manuals, you’ll find the same colorful wheel of 12 archetypes—the Hero, Lover, Rebel, Creator, Caregiver, and so on. These graphics spread rapidly because they promise clarity: a simple taxonomy to categorize every personality or brand. Yet this “12 Archetypes” framework did not originate with Jung.

It came from Carol Pearson’s Awakening the Heroes Within (1991), a valuable but modern re‑interpretation designed for personal and organizational development. Pearson’s twelve were inspired by Jungian themes yet adapted for a contemporary audience exploring “inner heroic journeys.”

Jung himself—ever a mystic scientist rather than a marketer—warned explicitly against reducing the archetypes to lists. He called them “complexes of experience that come upon us like fate.” That means archetypes act through us more than we choose them.

For more on this topic, see: Brand Archetypes: How to Apply Archetypal Psychology to Marketing

Common Questions About Jungian Archetypes

Let’s explore a few common questions related to Jungian archetypes:

Q: “What’s my Archetype?”

From my perspective, although numerous “archetype quizzes” and assessments are available online, this question and these themselves misunderstand the nature of archetypes.

One’s psyche is a composite of many different archetypes. In fact, different archetypes, parts, or subpersonalities shift within one’s psyche multiple times a day.

For example, changing clothes can trigger a different archetype. The music one listens to, and the media one watches, also trigger numerous archetypal patterns.

In my experience, pigeonholing yourself with one or a few archetypes isn’t practical or effective. If anything, it’s more likely to create unnecessary ego inflation. Instead, observe your habitual patterns—thoughts, feelings, attitudes, impulses, and judgments.

It is, however, useful to familiarize yourself with various archetypal patterns to increase your consciousness when you notice yourself possessed by one of them.

Q: What are Personality Archetypes?

I’m not sure where the term “personality archetypes” originates, but I’m reasonably sure it wasn’t Jung. Any archetype can (and does) influence your personality.

That said, virtually all personality models, including the Enneagram, Myers-Briggs, and Human Design Engineering, assess a series of personality archetypes.

For example, the nine types in the Enneagram are, in essence, nine different personality archetypes.

Type 1: Reformer / Perfectionist

Type 2: Helper / Giver

Type 3: Achiever / Performer

Type 4: Individualist / Romantic

Type 5: Investigator / Observer

Type 6: Loyalist / Loyal Skeptic

Type 7: Enthusiast / Epicure

Type 8: Challenger / Protector

Type 9: Peacemaker / Mediator

Similarly, all the combinations of Jung’s Psychological Types used in Myers-Briggs can also be considered personality archetypes.

However, as stated above, it’s an error to identify with a particular personality archetype. (For this reason, Jung dismissed the Myers-Briggs personality model as missing the point.)

Q: What are Character Archetypes?

Character archetypes are common characters found in story structure. All of the Jungian archetypes listed above are common patterns found in storytelling.

A classic example of a character archetype is the Hero. Another example would be Jung’s Wise Old Man, or what mythologist Joseph Campbell called the Mentor with supernatural aid.

Here’s a list of common character archetypes:

- The hero (protagonist)

- The villain (antagonist)

- The wise old man (mentor or sage)

- The trickster (manipulator)

- The princess (anima)

- Allies (friends)

- Magical animal (guide)

There are also many derivatives of these character archetypes. For example, I outline 10 variations of the hero archetype in this guide.

How to Work with Archetypes in Personal Growth

The aim of archetypal work isn’t to collect symbols but to cultivate a relationship with the living patterns inside you.

Jung called this ongoing dialogue conscious participation—allowing mythic energies to reveal their purpose without being ruled by them.

True transformation begins when you notice which archetype speaks through your choices, dreams, and voice. Observation comes first; meaning unfolds next.

Becoming Conscious of the Pattern

Each emotion, impulse, or recurring life theme signals an archetype at work. The Hero may appear whenever you chase an impossible challenge. The Caregiver shows when you sacrifice your own needs; the Trickster when sarcasm masks fear.

Start by recording strong emotional events as if you were documenting an internal play. Name the “characters” you sense in those moments.

Journaling, drawing, or speaking aloud personifies the pattern so you can meet it consciously. This awareness weakens possession—the state in which an archetype temporarily takes over behavior.

Over time, you’ll perceive a cast of inner figures shaping every decision and relationship.

Integrating, Not Imitating

Working with archetypes doesn’t mean acting them out. It means discerning when an archetype’s energy is distorted or balanced.

For example, the Shadow becomes destructive when denied but creative when integrated; the Lover matures into devotion when balanced by discernment.

Jung’s method of active imagination allows those energies to express themselves safely through image, dialogue, or movement until understanding dawns.

The goal is not perfection but wholeness—a psyche where every voice has a seat at the table.

Read Next

Jung and Alchemy: The 4 Stages of the Magnum Opus

Jungian Synchronicity Explained: The Psychology of Meaningful Coincidences

Spiritual Healers & Their Shadow: A Real-World Guide

This guide is part of the Jungian Psychology Series.

Explore in-depth frameworks on the unconscious, archetypes, and individuation—revealing how self-awareness transforms the psyche through Carl Jung’s analytical tradition.

References

- C.G. Jung (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Edward F. Edinger (1992). Ego and Archetype. C.G. Jung Foundation Books.

- Robert A. Johnson (1993). The Fisher King and the Handless Maiden. HarperOne.

- Carol Pearson (1991). Awakening the Heroes Within. Harper.

- Marie-Louise von Franz (2002). Animus and Anima in Fairy Tales. Inner City Books.