Every culture tells a version of the same story: a call to adventure, an ordeal, a hard‑won return.

Whether written in myth or lived in daily life, this sequence points to something deeper than plot—it’s the psyche’s story of evolution.

Joseph Campbell called this sequence the monomyth, a framework describing the journey all humans undertake when they confront their limits and awaken latent potential.

This guide—part of the Archetypes and Symbolism Series—invites you to see the Hero’s Journey not as fiction, but as a psychological process anyone can consciously undergo.

Let’s dive in …

What is the Hero’s Journey?

Every civilization tells the same essential story: a hero’s departure from comfort, a passage through tests, and a return carrying wisdom.

Campbell called this shared pattern the monomyth—a single thread running through ancient epics, tribal lore, and modern cinema alike.

Its endurance across centuries suggests that mythology is not entertainment but instruction—an operating manual for human development disguised as adventure.

When we read these tales, we’re not just witnessing some distant figure’s trial; our own psyche recognizes its reflection.

The Inner Map Behind the Myth

Beneath the dragons, deserts, and supernatural quests lies psychology.

Campbell and Jung both saw myth as the language of the unconscious—a system of symbols expressing the journey from instinct to awareness.

Each threshold crossed in story mirrors a threshold within us: fear confronted, belief challenged, identity shed.

The external adventure dramatizes a purely inner process—the growth of consciousness itself.

This is why the Hero’s Journey still resonates today: it reveals that meaning is not bestowed from the outside but forged through courage, failure, and reintegration of what was once rejected.

The Psychology Behind the Monomyth

At its heart, the Hero’s Journey isn’t about a man slaying monsters—it’s about consciousness evolving. Every myth you’ve ever heard is a coded message from the human psyche to itself.

Joseph Campbell discovered that the heroic path mirrors the way awareness grows: first by separating from the familiar, then by facing what it fears, and finally by returning as a fuller, freer being.

What we call “mythology” is simply psychology told in symbols—our oldest language for inner change.

What Myth Really Means in Psychology

Today, we use the word myth to mean “something untrue.”

Both Jung and Campbell restored its original sense: myth as metaphor for truth too large to explain directly. The gods, monsters, and enchanted lands were never literal—they were artistic ways to talk about emotion, instinct, and moral tests.

When ancient people shared myths around a fire, they weren’t escaping reality; they were interpreting it. Myth was philosophy before psychology existed—an early form of therapy expressed as story.

Myths, for Jung and Campbell, represent dreams of the collective psyche. In understanding the symbolic meaning of a myth, you come to know the psychological undercurrent—including hidden motivations, tensions, and desires—of the people, the culture, and oneself.

Who the Hero Actually Is (the Archetype Within)

The “Hero” isn’t a celebrity figure or historical warrior. He (or she) represents a recurring psychological archetype—a part of every person that longs to transcend limitation.

In Jungian terms, this is the archetype of transformation: the instinct to become whole. The dragons along the way are fears, the mentors are conscience and wisdom, and the treasure is self‑knowledge.

When we relate to the hero archetype, it’s because that same impulse stirs within us. Each life crisis—loss, change, creative struggle—is a personal call to adventure pressing us toward renewal.

Why the Hero’s Journey Still Works Today

Because it describes the structure of transformation itself, the monomyth continues to move us even when we don’t consciously believe in it.

When a film or novel follows that pattern, our unconscious recognizes the code: separation, ordeal, return. It feels authentic because it mirrors how growth feels inside us.

Campbell said mythology is “psychology misread as biography, history, and cosmology.” In truth, the Hero’s Journey is every person’s journey from ignorance to awareness, from fear to freedom—the essential cycle of becoming human.

The 3 Core Phases of the Hero’s Journey

Every psychological transformation unfolds in patterns.

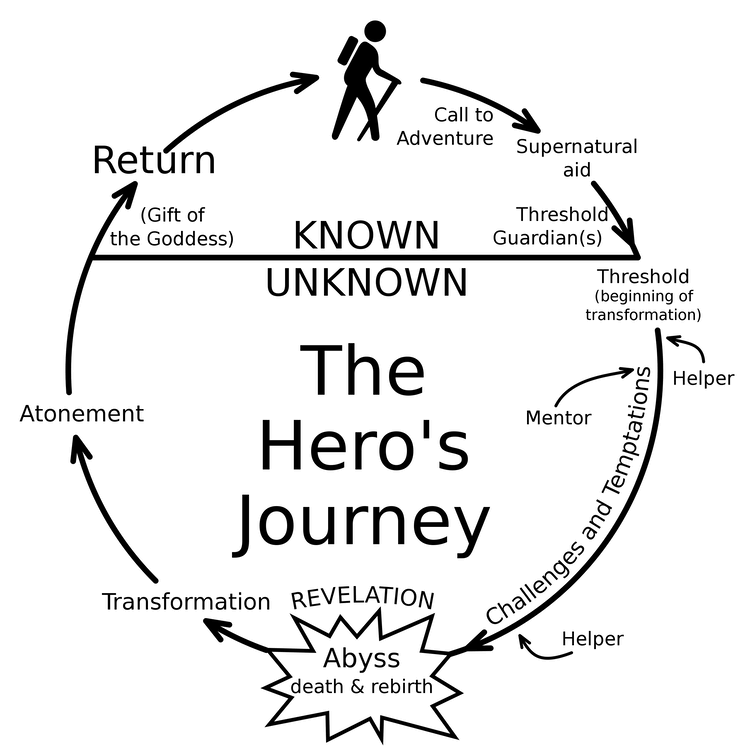

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell observed that all myths follow a single dynamic movement: a departure from the familiar, confrontation with the unknown, and integration of new consciousness.

These are not just story beats—they model how personal development occurs in real life. Each phase captures a different stage of growth: awakening, testing, and integration.

This cycle of coming and returning has three clear stages:

Stage 1: Departure — The Call to Adventure and Separation

The first stage begins when comfort becomes confinement. Campbell called it the call to adventure—that disorienting moment when routine no longer fits, and a deeper impulse pushes for change.

In psychological terms, this is the activation of disequilibrium: the psyche senses growth potential beyond its current identity.

The hero resists at first (the refusal of the call), but circumstances or crisis force movement. This step represents ego separation, the birth of individual consciousness out of collective conditioning.

Luke Skywalker leaves his home planet to join Obi-Wan to save the princess. Neo gets unplugged from The Matrix with the help of Morpheus and his crew.

In the Departure stage, you leave the safety of the world you know and enter the unknown.

Campbell explains:

This first step of the mythological journey—which we have designated the “call to adventure”—signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.

That is, the hero must leave the known “conventional world” and enter a “special world” that is foreign.

Stage 2: Initiation — Trials, Tests, and Transformation

Here, the individual faces inner and outer antagonists. Where stories show dragons or labyrinths, psychology sees shadow confrontation—encounters with aspects of ourselves we’ve denied.

Campbell’s phrase the road of trials captures the essence of learning through friction. Allies appear (mentors, archetypes of guidance), and opposing forces expose weakness.

Each conflict functions as a catalyst for neural and emotional reorganization: endurance, insight, and humility replace naïve confidence.

The Initiation phase transforms instinct into awareness—the key operation of every genuine psychological change process.

Stage 3: Return — Integration and the Gift of Wisdom

Transformation is incomplete until it’s applied. In myth, the hero brings back the elixir; in life, we return with perspective.

This phase symbolizes the assimilation of experience into daily behavior—a reconciliation between old patterns and new vision. It parallels what modern therapy calls integration: embodying insight through consistent action.

The reward isn’t adventure’s thrill but equilibrium—living from a matured identity capable of both strength and service.

Thus, the Hero’s Journey ends where it began, but consciousness has expanded; the world is the same, yet the one who perceives it is not.

Luke becomes a Jedi and makes peace with his past. Neo embraces his destiny and liberates himself from the conventions of The Matrix.

But the hero is no longer the same. The maturation process of the experience has transformed him internally.

The Hero’s Journey Structure in Plays and Drama

In Three Uses of a Knife (2000), famed playwright David Mamet highlights a similar three-act structure for plays and dramas:

Act 1: Thesis. The drama presents life as it is for the protagonist. The ordinary world.

Act 2: Antithesis. The protagonist faces opposing forces that send him into an upheaval (disharmony).

Act 3: Synthesis. The protagonist attempts to integrate the old life with the new one.

Problems, challenges, and upheavals are the defining characteristics of this journey.

Why? Without problems that trigger a “Call to Adventure,” the path toward growth is usually not taken. Instead, the comfort zone of the familiar, “ordinary world” continues to dominate one’s consciousness.

The Hero’s Journey in 12 Practical Steps

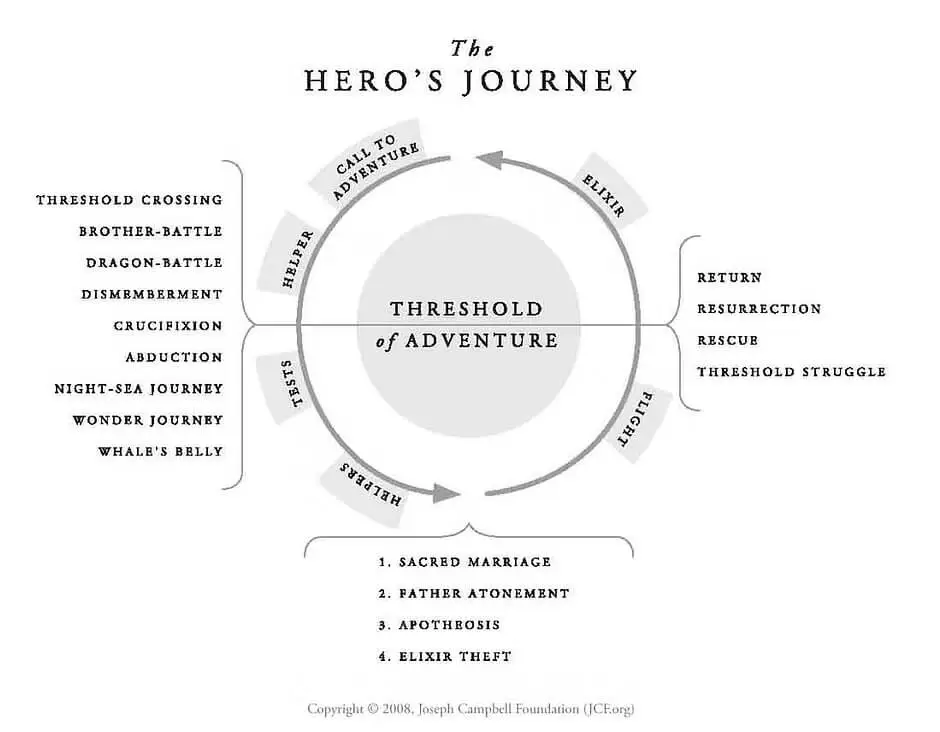

Mythologist Joseph Campbell outlined 17 stages of the monomyth in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949)—a detailed framework for understanding transformation.

Decades later, story analyst Christopher Vogler (2007) distilled Campbell’s map into 12 steps that mirrored modern narrative flow while preserving its psychological essence.

Nearly all contemporary interpretations—from Hollywood screenwriting to self‑mastery models—trace back to this synthesis.

In practical terms, Vogler’s adaptation endures because it reflects how transformation feels: a spiral from awakening to ordeal to renewal.

These 12 steps of the Hero’s Journey describe a universal path of change—from the ordinary world through trials of initiation to the return of self‑knowledge and purpose.

The following sections outline each stage as both a story pattern and a psychological process of growth and integration.

1 The Ordinary World — Life Before Awakening

The first stage begins when comfort becomes confinement. Campbell called it the call to adventure—that disorienting moment when routine no longer fits, and a deeper impulse pushes for change.

The ordinary world represents our norms, customs, conditioned beliefs, and unconscious drives and behaviors. It’s what Campbell called the “conventional world.”

In The Hobbit, the ordinary world is the Shire, where Bilbo Baggins lives with all the other Hobbits—gardening, eating, and celebrating—living a simple life. J.R.R. Tolkien contrasts this life in the Shire with the special world of wizards, warriors, men, elves, dwarves, and evil forces on the brink of world war.

In psychological terms, this is the activation of disequilibrium: the psyche senses growth potential beyond its current identity.

The hero resists at first (the refusal of the call), but circumstances or crisis force movement. This step represents ego separation, the birth of individual consciousness out of collective conditioning.

2 The Call to Adventure — Invitation to Transformation

Here, the individual faces inner and outer antagonists. Where stories show dragons or labyrinths, psychology sees shadow confrontation—encounters with aspects of ourselves we’ve denied.

Campbell’s phrase the road of trials captures the essence of learning through friction. Allies appear (mentors, archetypes of guidance), and opposing forces expose weakness.

Each conflict functions as a catalyst for neural and emotional reorganization: endurance, insight, and humility replace naïve confidence.

Obi-Wan told Luke, “You must come with me to Alderaan.” Thus, Luke was invited to leave the ordinary world of his aunt and uncle’s farm life and go on an adventure with a Jedi knight.

As Campbell explains, “The call to adventure signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of this society to a zone unknown.” That “unknown zone” is within.

The Initiation phase transforms instinct into awareness—the key operation of every genuine psychological change process.

3 Refusal of the Call — Resistance and Fear

Fear of change as well as death, however, often leads the hero to refuse the call to adventure.

Growth demands risk, so the ego defends its ground. Excuses, anxiety, or “rational” objections delay departure.

The ordinary world represents our comfort zone; the special world signifies the unknown.

Luke Skywalker immediately responds to Obi-Wan, “I can’t go with you,” citing his chores and responsibilities at home.

Psychologically, this is avoidance conditioning—an instinct to preserve safety. Yet refusal itself generates pressure; unresolved tension eventually propels movement.

4 Meeting the Mentor — Encounter with Wisdom

Guidance appears once readiness forms. The Mentor archetype—a teacher, book, dream, or inner voice—offers tools, clarity, or faith.

In Jungian terms, it represents contact with the Wise Old Man/Woman archetype, an image of intuition bridging ego and Self.

Campbell called this archetype the “mentor with supernatural aid.”

Generally, at an early stage of the adventure, the hero is graced by the presence of a wise sage. In stories, the mentor is personified as a magical counselor, a reclusive hermit, or a wise leader. The mentor’s role is to help guide the hero.

Think Obi-Wan, Yoda, Gandalf, Morpheus, or Dumbledore. Sometimes cloaked in mystery and secret language, a mentor manifests when the hero is ready.

Unfortunately, our modern world is depleted of wise elders or shamans who can effectively bless the younger generation. For most of us, it is best to seek spiritual guidance within.

5 Crossing the First Threshold — Commitment to Change

The hero moves from the known into the special world—from safety into uncertainty.

This crossing marks ego detachment, a psychological point of no return. Behavioral scientists might call it activation energy: the decision that turns possibility into action.

Although Luke initially refuses the call to adventure, upon returning home to find his aunt and uncle dead, he immediately agrees to accompany Obi-Wan. He crossed the first threshold.

In one sense, the first threshold is the point of no return. Once the hero shoots across the unstable suspension bridge, it bursts into flames. There’s no turning back.

6 Tests, Allies, and Enemies — Facing External and Internal Challenge

Progress breeds opposition. Trials expose weakness while allies reinforce courage.

These encounters externalize inner polarity: self‑doubt, projection, envy, integrity.

Each test strengthens adaptive capacity and clarifies values. In therapeutic terms, it is exposure and reconditioning.

Luke meets Obi-Wan (mentor), Han Solo, Princess Leia, and the Rebel Alliance while fighting many foes. Neo meets Morpheus (mentor), Trinity, and the rest of the Nebuchadnezzar crew while having to fight Agents in a strange world.

7 Approach to the Inmost Cave — Confronting the Shadow

Now the hero approaches the center of conflict—the shadow complex.

This “cave” symbolizes the unconscious: fears, desires, and wounds long avoided. Entering it is not regression but reclamation. The psyche gathers fragments of lost vitality hidden in repression.

Neo decides to go save Morpheus, who’s being held in a building filled with Agents.

The cornerstone of the special world lies within the walls of the innermost cave.

As neo-Jungian Robert Johnson explains, for a man, the innermost cave represents the Mother Complex, a regressive part of him that seeks to return to the safety of the mother.

When a man seeks safety and comfort—when he demands pampering—it means he’s engulfed within the innermost cave.

For a woman, the innermost cave often represents learning how to surrender to the healing power of nurturance—to heal the handless maiden (a common archetype within the feminine psyche).

8 Ordeal — Death and Rebirth

No worthwhile adventure is easy. There are many perils along one’s spiritual journey.

Every real change includes symbolic death. Old beliefs disintegrate; control loosens.

Campbell called this phase “the belly of the whale.” The individual surrenders to transformation, and something new begins organizing from within.

This is psychic metamorphosis—the crisis where consciousness expands or collapses.

A major obstacle confronts the hero, and the future begins to look dim: a trap, mental imprisonment, or imminent defeat on the battlefield. In these moments of despair, it feels like all hope is lost.

Here, the hero must access a hidden part within—one more micron of energy, strength, faith, or creativity—to find the way out of the belly of the beast.

Neo turns and confronts Agent Smith in the subway station—something that was never done before. The hero must call on an inner power it doesn’t know it possesses.

9 Reward — The Treasure of Insight

Having survived disintegration, the hero gains clarity or strength—the boon.

Externally, it might appear as achievement; internally, it is self‑knowledge.

Neural and emotional systems realign: a renewed sense of purpose, esteem, or peace emerges.

Having defeated the enemy and slain the dragon, the hero receives the prize. Pulling the metaphorical sword from the stone, the hero achieves the objective he set out to complete.

Whether the reward is monetary, physical, romantic, or spiritual, the hero undergoes an inner transformation.

10 The Road Back — Challenges in Integration

Alas, the adventure isn’t over yet. There is usually one last push needed to return home. Now the hero must return to the world from which he came with the sacred elixir.

Challenges, such as villains, roadblocks, and inner demons, still lie ahead. At this stage of the journey, the hero must deal with whatever issues remain unresolved.

Returning to the context of ordinary life tests whether the transformation endures. Old circumstances re‑emerge, tempting relapse.

In therapeutic language, this is reintegration under stress. Sustaining change demands vigilance and the humility to relearn balance.

Taking moral inventory, examining the Shadow, and performing self-inquiry help the hero identify weaknesses and blind spots that will later play against him.

11 Resurrection — Final Trial of Identity

Before returning home—before the adventure is over—there’s often one more unsuspected, unforeseen ordeal.

This final threshold, which may be more difficult than the prior moment of despair, provides one last test to solidify the hero’s spiritual growth. It represents the final climax.

The last ordeal re‑examines attachment to the ego. It’s often the crisis of integration: can wisdom survive contact with reality?

Here, the hero demonstrates authentic alignment between insight and action. Symbolically, it is resurrection—the rebirth of consciousness at a higher order.

Neo is shot and killed by Agent Smith. And, he literally resurrects to confront the enemy one last time following his transformation.

The uncertain Luke Skywalker takes that “one in a million” shot from his X-Wing to destroy the Death Star.

12 Return with the Elixir — Sharing the Gift

The journey concludes with contribution. The hero re‑enters ordinary life carrying knowledge, compassion, or creative power to uplift others.

This final stage completes the feedback loop of development: self‑realization expressed as service.

In Jungian terms, the Self now directs the personality rather than the other way around.

In this final stage, the hero can become the master of both worlds, with the freedom to live and grow, impacting all of humanity.

Returning with the prize, the hero’s experience of reality is different. The person is no longer an innocent child or adolescent seeking excitement or adventure.

Comfortable in its own skin, the hero has evolved and is now capable of gracefully handling the demands and challenges of everyday life.

Hollywood and the Hero’s Journey

George Lucas was friends with Joseph Campbell. Lucas used these hero’s journey steps from Campbell’s work to produce the original Star Wars film.

It’s difficult to appreciate the impact Star Wars still has on American culture and around the world. It’s even more challenging to articulate how much of that impact is attributed to Campbell’s insights.

However, one challenge modern culture faces is that many popular film franchises never complete the hero’s journey. Popular characters in action films, such as Marvel and DC Comics superheroes, James Bond, Ethan Hunt (Mission: Impossible), and Indiana Jones, never genuinely transform.

These characters stay in the adolescent stage of development (and modern culture tends to celebrate that reality). These heroes don’t evolve into the warm, vulnerable, generative adults who no longer seek adventure and excitement.

That said, since I originally published this guide in early 2018, this has begun to change. For example, in the final Bond film, No Time to Die (2021), James Bond demonstrated some generative growth. The same goes for Tony Stark’s character (Iron Man) in Avengers: Endgame (2019).

Mapping the Hero’s Journey to Modern Life

The Monomyth isn’t locked in ancient legend—it’s the operating system of growth itself. Campbell called mythology “the song of the universe,” but its rhythm plays quietly in modern experience.

Every breakup, career change, illness, creative risk, or awakening follows this same pattern: a call, resistance, initiation, and new equilibrium.

When we understand this structure psychologically, life’s chaos begins to feel coherent. Events aren’t random obstacles—they’re evolutionary invitations.

Departure in Everyday Life — The Crisis of Comfort

A “call to adventure” today might appear as burnout, restlessness, or quiet dissatisfaction. The psyche signals that its existing map no longer supports growth.

In neuropsychology, this is disequilibrium: tension between what you know and what you’re capable of becoming.

Leaving the “ordinary world” means stepping beyond social scripts, even before you’re ready.

Initiation — Turning Difficulty into Development

Our modern “trials” don’t involve fighting dragons but managing uncertainty, emotional triggers, or inner critics. Therapists might describe this as shadow integration—meeting repressed emotions with awareness.

Each challenge rewires neural expectation, building flexibility. Through honest struggle, we metabolize experience into wisdom; through avoidance, we repeat cycles until we learn.

Return — Living Beyond Survival

After transformation, integration becomes the quiet art of embodiment. Insight only matters when it enters behavior. Bringing back the elixir might mean expressing creativity, repairing relationships, or mentoring others through similar change.

In depth psychology, this is Self‑actualization: aligning daily action with inner truth. The journey’s close is really the beginning of full participation in life.

A Modern Call to Adventure — Self‑Actualization as Service

In ancient myths, the hero healed a kingdom by returning with new knowledge. Today, genuine service is a metric of maturity.

Personal transformation ripens when it benefits collective well‑being—family, community, or culture. This social recursion is why the Hero’s Journey remains relevant: it transforms self‑improvement into contribution, evolution into empathy.

Why the Hero’s Journey Still Matters

Every generation rediscovers the Hero’s Journey because it speaks to something perennial in the human psyche. We are wired to learn through story: narrative gives emotion a shape the mind can metabolize.

Joseph Campbell described myths as “the masks of eternity”—symbols through which consciousness contemplates its own evolution. Even in an age of algorithms, our deepest programming still runs on story.

When people feel directionless or fragmented, the Hero’s Journey restores coherence. It reminds us that pain and confusion are not random; they are signals that transformation is in progress. The same cycle guiding ancient heroes guides us through psychological renewal today.

The Hero’s Journey matters because it translates chaos into meaning. It turns personal struggle into a structured process of learning, reintegration, and service.

Myth as Modern Medicine

Science addresses symptoms; myth addresses sense. As anxiety and burnout rise, the imagination hungers for a holistic framework that restores purpose.

The Hero’s Journey provides just that—a developmental narrative that links neuroscience (pattern recognition), depth psychology (archetypal imagery), and mindfulness (presence under pressure).

In practical terms, it’s a mental model that helps the brain encode challenges as growth signals, not threats.

Story as Neural Mapping

Contemporary cognitive research confirms what Campbell intuited: story structure mirrors brain structure.

We remember information organized as narrative because it parallels episodic memory sequencing (Byrne and Burgess, 2007).

The 12 steps resonate not by mythic coincidence but by cognitive design.

When we position ourselves as protagonists facing change, the prefrontal cortex reframes stress as meaning, enhancing resilience. That’s why storytelling—and self‑storying—remains psychologically therapeutic.

The Ethical Arc of Transformation

The journey doesn’t culminate in victory but integration. As Campbell said, “The goal of the hero’s journey is not power but wisdom.”

Modern life often celebrates endless escalation—more success, more exposure—but neglects return with the elixir: using insight for collective good.

The Hero’s Journey endures because it codifies maturity—how experience becomes empathy and individual realization becomes inner contentment, and often, contribution.

Applying the Archetype Consciously

The Hero’s Journey ends not with triumph but with awareness. To “apply the archetype consciously” means to live the myth with eyes open, to:

- Recognize when an old identity is dissolving,

- Stay present through uncertainty, and

- Bring insight back into behavior.

Carl Jung called this process individuation—the lifelong integration of unconscious patterns into a coherent, grounded Self.

When we approach experience through this lens, obstacles cease to feel arbitrary. They become symbols: every discouraging event is another stage of transformation seeking expression.

Conscious archetypal work is the practice of recognizing mythic patterns—like the Hero, Mentor, or Shadow—as inner dynamics guiding psychological growth and decision‑making.

Recognize the Archetype at Play

Begin by naming the dynamics shaping your current phase.

- Are you resisting change (Refusal of the Call)?

- Seeking teachers (Meeting the Mentor)?

- Facing emotional patterns that mirror the Shadow?

Labeling the pattern converts overwhelm into orientation; it tells the nervous system, I am in process.

This simple awareness moves experience from unconscious reactivity to conscious participation—an essential step in stress regulation and meaning‑making.

Dialogue with the Unconscious

Jung emphasized active imagination—allowing images, dreams, and intuitions to speak without censorship.

Consciously engaging the archetype means tracing emotion back to symbol: the dragon may represent insecurity; the cave, introspection.

Meditation, journaling, or creative work turns this dialogue into integration, building communication between conscious and unconscious systems.

Transform Insight into Embodiment

Awareness alone doesn’t complete the cycle; transformation happens only when insight enters muscle memory.

That requires iterative practice—new behaviors aligned with new understanding.

For example, courage discovered in meditation must be enacted as conversation, risk, or creative leap. This behavioral embodiment is what converts mythological realization into lasting neural re‑patterning.

Service as Final Integration

The last measure of maturity is service.

In Campbell’s language, returning with the elixir means sharing your earned wisdom—not proselytizing, but embodying compassion and skill that uplift others.

Psychologically, this closes the feedback loop: experience → meaning → embodiment → altruism.

Each act of contribution stabilizes the individual in the new Self and prevents regression into the former ego pattern.

Conclusion: The Cycle Continues

Every stage of the Hero’s Journey is both an ending and a beginning.

The myth repeats not because life circles aimlessly, but because consciousness evolves in spirals.

Each time we face uncertainty, an older pattern dies, and a wiser Self takes shape.

Campbell wrote that “the cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek”—and that treasure, once found, will eventually call you forward again.

To live mythically is to live awake: aware that ordeals are initiations, that loss hides renewal, and that meaning is handcrafted through our decisions.

Seen this way, day‑to‑day existence becomes the classroom of individuation. The Hero’s Journey is the map; your awareness is the compass.

Returning to Wholeness

When you integrate experience rather than escape it, you enact the essence of myth.

Your greatest contribution arises naturally from that wholeness—whether art, teaching, parenting, or quiet integrity.

The Hero archetype matures into the Sage and the Creator, expanding the cycle from self‑transformation to world‑building. This is how individual evolution nourishes collective renewal.

Continuing Your Journey

The CEOsage Knowledge Center exists to accompany seekers through successive arcs of development—from Jungian Psychology and Archetypes to Energy Science and Creativity to Leadership and Self-Actualization.

Each hub functions like the next threshold of the monomyth: new terrain, same underlying process. Wherever you feel the pull of curiosity, follow it. That impulse is the next call to adventure.

Recommended Books

The hero’s journey steps are outlined in the books referenced throughout this guide:

The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell

Joseph Campbell’s Mythos Lecture Series (The Complete Series)

How to Be an Adult by David Richo

Read Next

Jungian Synchronicity Explained: The Psychology of Meaningful Coincidences

The 3 Stages of Spiritual Growth: From Self‑Discovery to Self‑Realization

What Is a Spiritual Journey? An Insider Guide to Transformation

King Warrior Magician Lover: Four Foundational Masculine Archetypes

This guide is part of the Archetypes & Symbolism Series.

Discover the universal patterns shaping every story, dream, and relationship. These Jungian and symbolic guides decode the timeless forces guiding behavior and creativity.

For deeper context on the unconscious and development, see the Jungian Psychology Series.

References

- Byrne, P., Becker, S., & Burgess, N. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: a neural model of spatial memory and imagery. Psychological review, 114(2), 340–375.

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

- Campbell, J. (1988). The Power of Myth. Doubleday.

- Campbell, J. (1990). The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell on his life and work. Harper & Row.

- Campbell, J. (1991). Reflections on the Art of Living: A Joseph Campbell Companion. Harper Perennial.

- Gottschall, J. (2012). The Storytelling Animal: How stories make us human. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Johnson, R. A. (1989). He: Understanding Masculine Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Johnson, R. A. (1995). The Fisher King and the Handless Maiden: Understanding the wounded feeling function in masculine and feminine psychology. Harper Perennial.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Richo, D. (1999). How to be an Adult: A handbook on Psychological and Spiritual Integration. Paulist Press.

- Vogler, C. (1992). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Michael Wiese Productions.

I would like to understand the Hero’s journey. Joseph Campbell describes it as something that has been taken/lost or life giving. How do I know if my hero’s journey has been done?

If you’re examining the hero’s journey from the perspective of individuation — that is, the journey to mature adulthood — it takes many years to come to wholeness within oneself.

Psychologically speaking, the hero’s journey is inward. The characters you meet (like the Mentor) are within yourself. So it involves active imagination in bringing the archetype into some form of harmony within yourself.

You have mentioned a choice to stay in the comfort of safety or the unknow for growth. I am wondering if this is done in a Psychological manner where your life’s circumstances stay as they are or you physically live in a different environment, leaving your surroundings, people and material responsibilities etc.. Hope you can answer this for me.

If you’re a young adult, there’s often an external aspect to the hero’s journey — for example, leaving home and separating from one’s parents. But what Campbell was highlighting with the monomyth is ultimately a psychological process akin to Jungian individuation:

https://scottjeffrey.com/individuation-process/

I want to share my thoughts on the heroes journey. After reading the twelve steps, and what you said- I quote “Step 12: Return with the Elixir

Often, the prize the hero initially sought (in Step 9) becomes secondary as a result of the personal transformation he undergoes.

Perhaps the original quest was financially driven, but now the hero takes greater satisfaction in serving others in need.

The real change is always internal.

In this final stage, the hero can become the master of both worlds, with the freedom to live and grow, impacting all of humanity.”

My favorite movie for a while now has been The Peaceful Warrior, I have just watched Coach Carter. They seem to tell the same story and I think the story of The Heroes Journey. You have mentioned Star Wars, James Bond and the Matrix.

In the movies The Peaceful Warrior, and Coach Carter, the achievement earned is an inward spiritualism that is, I quote” impacting all of humanity.” Thank-you.

If The Peaceful Warrior is your favorite movie, read Dan Millman’s “The Way of the Peaceful Warrior” — the book the film is based on. Much deeper insights. It’s a magical book — especially when you’re just setting out on your self-discovery journey.

I have read about 25% so far, I am not a good reader. I give myself three pages each day, yet often I’m reading more. It is as if the movie is replaying and I’m able to go with it, imaging the main characters.

There is more information from reading than watching the movie, though I am thinking there is a lot of fiction, as it has been described on the net. Though I just need to adhere to the believable parts.

I don’t know if it is possible to remember the day’s events that happened during college. For example, what people said, what they were doing throughout the day.

My college day’s I can only remember situations that happened all dispersed from one another, with only a few minutes recalled. Does someone like yourself able to recall conversations and put them as dialogs for a book? Or is it a writer’s privilege to invent these for the book?

“The Peaceful Warrior” is a work of fiction. The genre is technically called “visionary fiction.”

There is a passage in the book where Socrates say’s “Mind is an illusory reflection of cerebral fidgeting. It comprises all the random uncontrolled thoughts that bubble into awareness from the subconscious. Consciousness is not the mind; awareness is not mind; attention is not mind. Mind is an obstruction, an aggravation, a primal weakness in the human experiment. It is a kind of evolutionary mistake in the human being. I have no use for the mind.”

I don’t think think this way because what we have as humans is natural and so

it has a purpose. I am interested if you would give an opinion on this statement Socrates said.

For the most part, I agree with Millman’s statements. They are also consistent with much of the Eastern traditions. An essential aspect of the meditative traditions is to “pacify the mind”. They sometimes even use stronger longer of “killing the mind.” But at other times, they make the distinction between the “aware mind” versus the “monkey mind” or the “shining mind” versus the “stirring mind.” But in terms of the untrained mind (which is the mind of over 99% of people), I agree with Millman. I just wouldn’t call it “evolutionary.”

Millman would have already made ethical judgment towards any begger, so, he should not have thought twice about ignoring him. But because his story, is going through a transformation, he had these menacing mind talks.

Do you think if you were in the same situation as him, would you give the begger money or use your self-consciousness to clear negative mind noise? I am wondering if a second time in the same situation would make one change their reaction…

This is quoted from the book;

“A scrawny young teenager came up to me. “Spare some change, can’t you?” “No, sorry,” I said, not feeling sorry at all. As I walked away I thought, “Get a job.” Then vague guilts came into my mind; I’d said no to a penniless beggar. Angry thoughts arose. “He shouldn’t walk up to people like that!” I was halfway down the block before I realized all the mental noise i had tuned in to, and the tension it was causing – just because some guy had asked me for money and I’d said no. In that instant I let it go.”

I finished the peaceful warrior and found it enjoyable. The preview of Dan’s second book (Sacred Journey of the peaceful warrior) sums up what he was expressing through his life.

There was one part I have heard before where the dialog between Dan and Soc was flat, with no meaning. Thank-you.

I would like to balance the four functions Jung describes (thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition) in your Individuation Process page. How do I know when feeling and sensation are active in everyday events? Could you give me an example? Thank-you.

Brett, please use the related guide page to address your questions.

The Individuation process page has not got a comments section.

I was walking in the bush on a moonlit windy night. The moving branches displayed a moving shadow, I was startled at first thought someone was behind me. Then I put the moonlight and the moving branches together and summed up what had happened without turning around. Was my thinking a Feeling, thinking, intuition or sensation? Thank-you.

I didn’t realize the comment sections weren’t open on that other guide. The psychological types represent our dominant orientations for processing information. When you were startled, was your attention on your body or the fear itself? Was your mind focused on “what could that be”? No need to answer here.

But the main thing about psychological types, from a Jungian perspective, is to understand what your dominant and inferior types are so you can develop your weakest side. Taking an Enneagram assessment test can help you determine your dominant type. In that system, it’s either thinking, feeling, or sensing.

Thank-you for your reply. You gave me an example of what I believe would be my dominant (being the first impression of the event) type. The second instance you described, is that too my dominant type? I do already know what it was that brings me fear. Can you follow up with this scenario? I have done enneagram questions before, and I am hopeless in giving a true response as all multiple question apply to equally.

“I have done enneagram questions before, and I am hopeless in giving a true response as all multiple question apply to equally.”

In my experience, when people say things like this, it’s often because they are “out of center” and analyzing things in their heads. If, for example, you read detailed descriptions of each Type, there’s no way you’re going to relate equally to all of them. Only one (sometimes a few) will strike a deep cord within you. It may leave you feeling “raw” and exposed.

Using the example you provided isn’t really going to help in this context. Do you mostly live in your head (mind/thoughts/analysis), your body (gut/sensations/sensory perception), or feelings? We all use all of them, but one tends to be more dominant than the others.

Thank-you. I agree with you Quote “If, for example, you read detailed descriptions of each Type, there’s no way you’re going to relate equally to all of them”. You might think I’m procrastinating as I want to work this out. Quote” Superior Function versus Inferior Function

We like to do things we’re good at and avoid doing things in which we feel inadequate.

Thus, we develop specific skills while undeveloped capacities remain in the unconscious.

Jung grouped these four functions into pairs: thinking and feeling, sensing and intuiting”. Follow me for a sec, I have determined my superior function is Thinking, that would leave my inferior function to feeling. I assume sensing and intuition would be in the middle. I’m going to give the answer that you will give to my question, how do I bring the four functions to the middle? Answer ; center yourself. Do you agree or tell me what I should be doing?

Brett, I can’t really speak to what you should be doing. From a Jungian perspective (as well as transpersonal psychology), you would develop your inferior function and grow in that line of intelligence. I borrow the concept of the Center from the Taoist tradition. Western psychology mainly seeks to build a healthy ego while Eastern traditions mainly focus on transcending the ego.

Is the answer to “center yourself”? Sure. But most likely you’ll only be able to do this temporarily (representing a “state” of consciousness), while if you develop via various practices, you establish different structural changes that become more stable.

How to Center Yourself.

I like this article and want to learn more. I’m sending you my questions in this article as there isn’t a comments section.

I have so many questions, do I really need these answered to be comfortable with learning? Or should I take a calming with acceptance approach, that will eventually find the answers I seek? Should I go ahead and ask… ok I will ask. In the four centers, take in information via the physical center, interpret experience via the emotional center, evaluate the world via the mental center. Could all be take in information? Thank-you.

Brett, I just opened the comment section on that centering guide. Please post your question there and then I’ll reply.

Is it always a Heroes journey to take on what seems an insurmountable task? I see this at the beginning of inspirational films. Thank-you.

Always be careful with the term “always.”

Remember that what Campbell was ultimately highlighting with his monomyth structure was a psychological process of development. So it’s best to keep that in context.

Insurmountable tasks can sometimes be a catalyst for one’s journey, but this is not always the case.

In films and storytelling, you need major a problem for the hero/protagonist to face. Otherwise, there’s no story.

With what you said in keeping the psychological process in context. I was thinking of the film where a football coach leaves a successful career in the city, to coach no-hoper orphans in the country. My first impression was that the coach is on a hero’s journey with much to lose but great inward comfort to gain.

Now I think it is the orphan footballers who are on a hero’s journey, (by leading as an example of being an orphan and becoming successful to inspire them to do the same) to stand up with confidence to be equal to the rest of the world.

The movie is twelve mighty orphans. Is this reasonable thinking and do you see different interpretation? Thank-you

I can’t really comment as I haven’t seen the film. In any decent film, multiple characters have “arcs.” In many cases, the coach in sports films plays the mentor/sage role but then has his own transformation as well. This is the case with Gandalf the Gray who has to “die” and be resurrected, transforming into Gandalf the White.

Merry Christmas Scott digital guide. Type to you soon:)

Does the hero’s journey have the same thoughts and feelings for a woman as a man?

From a Jungian perspective, the process would be different.

As Jungian Robert A. Johnson highlights in many of his books, the myths related to the feminine psyche are different than the myths related to the masculine. As such, they follow a different structure and aim.

That said, because there’s an anima in each male psyche and an animus in each female psyche, a part of us can relate to the hero’s journey in its totality. Hence, a heroine can go on a similar hero’s journey as a man.

What an excellent and thorough treatment. Thanks for these invaluable insights for my writing class.

Thank you for the feedback, Craig!

I love this observation about modern cinematic heroes: “Many popular characters in action films like Marvel and DC Comics superheroes, James Bond, Ethan Hunt (Mission Impossible), Indiana Jones, etc. never actually transform.”

Have you written elsewhere at greater length on this topic? I thought I read an article on this topic a few years back but don’t remember where! Certainly the weightiness of the observation was such a lightbulb moment.

Thanks and kind regards

M.

You can find a more detailed archetypal decoding of the hero here:

https://scottjeffrey.com/hero-archetype/